ICU Emeritus Professor and Former JICUF Trustee Benjamin Duke Writes Book about “Japanese Invasion” of Rutgers College 150 Years Ago

According to William Elliot Griffis who witnessed it, a “Japanese Invasion” of over 100 Japanese samurai youth took place in New Brunswick, New Jersey, beginning in 1866, one year after the American Civil War. Two Japanese boys, trained as warriors in feudal Tokugawa Japan, appeared unexpectedly on the campus of Rutgers College seeking a western education to prepare them to lead their country into the modern world. Over a hundred would follow them during the next ten years.

Dr. Benjamin Duke, while a trustee of the Japan International Christian University Foundation (JICUF) for nine years upon retirement from ICU after a forty-year career on the faculty, wrote a book on the consequences of the Japanese Invasion in New Jersey. While devoting many hours of research in the ICU library during his last years on the faculty to write a book entitled “The History of Modern Japanese Education” (Rutgers University Press, 2009), he discovered the roots of a little-known tale of the Japanese samurai in New Jersey.

Among the fascinating discoveries by Dr. Duke were the two routes followed by the hundred samurai youth from Japan to New Jersey in the 1860-70s. One was the direct route from Nagasaki initiated by a Christian missionary of the Dutch Reformed Church of America who was allowed into the heretofore closed nation in 1859 by a treaty forced upon the Tokugawa government in 1854 by Commodore Perry. The other route illegally followed by fifteen students from Satsuma in 1865 took them to London where they first enrolled for two years in the science department of University College London, later renamed the University of London. The Satsuma students then found their way to Rutgers College in America to join the others from Nagasaki. Ironically, many years later Benjamin Duke earned his PhD at the University of London under Professor Ronald Dore, Britain’s leading scholar on Tokugawa Japan, while on leave from ICU.

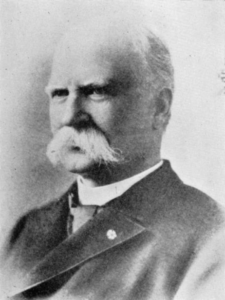

Dr. Duke’s last book of seven on Japanese education titled “Dr. David Murray: Superintendent of Education in the Empire of Japan 1873-1879,” Rutgers University Press, 2019, begins with Murray’s awakening to Japan on the campus of Rutgers College where he unexpectedly encountered the samurai youth in his mathematics class. He was so deeply impressed by their ‘quickness of powers, aptness for learning, and integrity of purpose’ that the Murrays opened their home as a social center for the Japanese students far from home. He described them as “models of courtesy, quickness, and diligence.”

Coincidentally, in 1872 the Japanese government sent a 50-member delegation of senior political leaders to Washington to begin negotiations to establish diplomatic relations. They were also searching for a western advisor to the Ministry of Education implementing the first national school system for Japan under Emperor Meiji. By then Murray had become fascinated with the han schools for samurai boys as he learned about them from the students enrolled in his classes at Rutgers. He was interviewed for the position in Washington and was appointed Superintendent in the Ministry of Education with a salary of $7,200. In comparison Dr. Duke’s salary at ICU in the 1960s was $4,800.

Part two of the book concerns the five and a half years that David Murray was employed as Superintendent of Japanese Education in the service of the Emperor. The high point of his tenure occurred in 1874 when the samurai student the Murrays treated as a son at Rutgers College, Hatakeyama Yoshinari, was appointed president of Kaisei Gakko while simultaneously serving as an aide to Murray in the Ministry. At the same time the two faculty members teaching science at the school were William Elliot Griffis and Edward Warren Clark, former students of Murray’s at Rutgers College in his Celebrated Class of 1868 that also included Hatakeyama. In 1877, Kaisei Gakko was reformed with Murray’s advice and renamed Tokyo University. David Murray was then chosen to give the congratulatory lecture at the first graduating class of Japan’s premier national university.

Two of the major conclusions in Dr. Duke’s book assert that Rutgers College made the greatest contribution to modern Japanese education among all educational institutions outside Japan, and that David Murray made the greatest contribution to modern Japanese education among all non-Japanese in the service of Emperor Meiji. Never before seen in print, these assertions originated while the author was conducting research at the ICU library in Japan and were recorded in print when he wrote the Murray biography while a Trustee of the Japan ICU Foundation in America.