Alumni Stories No. 17 – Fusae Nara

My first time on the Mitaka campus was August 1978, a few days after my return from West Germany. My mother’s best friend’s younger brother was an ICU alumnus, so I had some knowledge of the university from a young age. Having gone through the public school system though, I never imagined that I would actually attend the school.

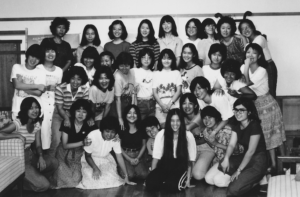

I first visited with my father, who was back in Japan on a work trip. Although it was still summer break, Ms. Himeko Kawakami of the Student Affairs office showed me around the First Women’s Dorm. Although I matriculated in September, I had never left the country before high school. My only international experience was moving to Dusseldorf when my father was transferred there and attending an international high school for two years. My English skills were lacking for a September student, and I spent most of my time with April students.

At the time, enrolling with this type of background exempted you from the FEP (Freshman English Program) and the Special Japanese course which allowed me to immediately take courses in Gen Ed and major requirements. At the international high school, my low English abilities meant that math, my weakest subject in Japan, was actually one of my strongest subjects. Since my TOEFL and SAT English scores were also low, upon enrolling I tried for a major in mathematics; however, trying to pursue my worst subject at the college level was disastrous for my grades. I immediately switched to social sciences my second year with a focus on international law. I took classes by Prof. Yozo Yokota and enrolled in the GSPA (Graduate School of Public Administration) with intentions of becoming an international civil servant, but in the midst of my studies I took an interest in the private sector and began working at the Japan Victor Company (currently JVC Kenwood Holdings Inc.) after completing the GSPA program. When I entered the company in 1985, the Equal Opportunity Employment Law had yet to go into effect, so discriminating against women wasn’t illegal and different standards of dress, duties, and demeanor were commonplace. Even so, I was blessed with good superiors and tasked with handling trade issues right in the middle of the Bubble. I gained experience researching anti-dumping and economic sanctions while developing a resentment for Japan bashing.

I had studied public international law at ICU, so I had a lot of catching up to do with U.S. and EU trade laws. It was during this time that I got to know the lawyers of major Western law firms. As I gained more work experience, I began to notice that these firms recruited the best and brightest representatives to handle international relations, but lacked understanding of Japanese business culture which made them ineffective. At the same time, I began to see the “glass ceiling” within my own company and decided that I wanted to study law in America and become a lawyer that could represent Japanese businesses effectively.

Researching international study destinations wasn’t possible on the internet in the 1980s, so I took advantage of what little resources there were and asked those with experience, such as Prof. Toshiki Mogami at ICU. He informed me that I could get an American law certification through the three-year Juris Doctor program, and also suggested applying to the relatively new, up-and-coming Hofstra School of Law to avoid the fierce competition for the most popular law schools. He also recommended offsetting the expensive tuition by applying for a CWAJ (College Women’s Association of Japan) scholarship – all incredibly useful pieces of advice. Sure enough, after being rejected from Columbia and NYU, I enrolled in Hofstra Law School in 1988.

Ms. Kumiko Chaki, my senpai from the Prof. Yokota seminar days, had a job relating to human affairs at the UN and was gracious enough to pick me up at JFK Airport and give me a place to stay until my studies began. Ms. Setsuko Yamazaki, another senpai of mine from GSPA, was also in New York working at UNDP and supported my adjustment to living in America. My studies were more difficult than I had imagined, and they both graciously lent an ear to my grievances over the phone throughout the year. After my first semester, I considered dropping out and returning to Japan, but by the second semester, I had gotten used to things and was even chosen as an editor for the Law Review. Joining the Law Review editorial team opened up a lot of job opportunities, and by the end of my second year, I had secured a summer associate program internship at a major law firm. The bubble was continuing in Japan, and many people suggested that I become a M&A (mergers & acquisitions) lawyer. I got a taste of this through my internship, but ultimately decided that I was better suited for trade and commerce law. After graduating, I got a position as a law clerk for two years at the U.S. Court of International Trade that specialized in trade and tariff laws. I was surprised by the openness of American society that allowed foreign nationals to work in the federal sector.

The bubble finally burst during my time at the court, and after my time as a law clerk ended in 1993, finding a job was a nightmare. After soliciting advice from dozens of people, I was finally able to meet a lawyer who worked with Japanese companies on trade issues and began my dream-job. However, anti-dumping only becomes an issue when imports to America increase and American companies suffer. By the mid-90s when the Japanese economy began to stagnate, new investigations were almost nonexistent – my superior quipped “Fusae, you were 10 years late becoming a lawyer.” I couldn’t bring myself to turn tail back to Japan after having worked so hard through law school, so afterwards I worked more broadly with civil suits involving Japanese corporations. Over the course of 25 years, I had the good fortune to work on a wide range of cases: antitrust law, violation of unfair trade practice regulations, breach of contract, intellectual property rights (patents, trademark rights) and class action lawsuits.

There are plenty of Japanese nationals with American law degrees, but few specialize in litigation and people are sometimes surprised that I am one of them. The process of discovery (having to comply with requests from the other party to produce evidence) is much different than Japanese civil law and can often be a cause of distress or frustration for Japanese corporations experiencing American litigation for the first time. After explaining the reasoning behind the American process to numerous clients, I began to realize that their frustration was the same as that I had felt while working in the “Japan bashing” atmosphere of my trade law days. 10 years after becoming a lawyer, rather than feeling I had become a lawyer too late, I was finally beginning to feel like the reason I studied law in the first place was becoming a reality.

The 10 years that followed were a blur of work, but recently I have begun looking at my career in retrospect. Looking back, I feel that moving to West Germany at 16 and subsequently enrolling in ICU was a major turning point in my life that eventually allowed me to do fulfilling work in a city that I love. Perhaps thanks to living in the dorms, I felt that campus was a spectacular atmosphere where there were no taboos in conversation and that speaking my mind was encouraged. As a freshman I met my husband (we both graduated at the same time, despite him being two years my senior) and we married immediately after I submitted my master’s thesis. We still cherish our memories at ICU after 40+ years together, and still reminisce on our time on campus.

While raising our two children here, I was surprised by the strong alumni network through all educational levels, from kindergarten to college, that continues to support their alma mater with donations and volunteer work. It got me to participate more often in ICU reunions and JICUF events and I learned a lot about things like ICU’s founding, or how JICUF’s work was revived by a bequest from Donald Othmer. I came to the strong realization that the opportunity for an education that allowed me to achieve my professional dream was the result of a combination of efforts from many different people.

Living in New York I occasionally have the joyous opportunity to meet with a fellow alum, but lately I hear that the number of Japanese students seeking to study abroad is diminishing. And it’s true: the number of Japanese students studying law abroad is plummeting compared to other East Asian countries like China and Korea. However, last year I had the opportunity to meet with Prof Hiromichi Matsuda and the ICU moot court team through an introduction by JICUF, as well as students interested in a future career in law, and I felt reassured by the enthusiasm of the current generation of ICU students.

The future of American society is uncertain not only with the spread of COVID-19 but with intensifying racial issues as evidenced by the surge of the Black Lives Matter movement These problems present themselves in a way that is unique to a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural country like America, but the diversity also creates an overwhelmingly positive energy and there is a lot to learn from America. Looking forward, I would like to use my experiences to navigate the future and continue to do my part to build bridges between Japan and America.