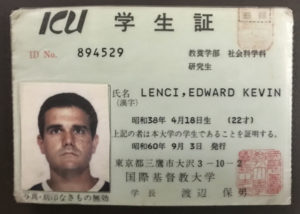

Alumni Stories #20 – Mr. Edward K. Lenci

Mr. Edward K. Lenci, who practices law in New York City, studied at ICU as a kenkyusei (research student) from 1985 to 1986. As the incoming Chair of the International Section of the New York State Bar Association (NYSBA), he was recently asked to write an article about the year he spent in Japan to mark Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. Last week, the NYSBA and the Osaka Bar Association (OBA) entered a Memorandum of Friendship, and the OBA translated the article into Japanese to circulate among lawyers in Osaka. We are happy to share this article and translation as part of our “Alumni Stories” series.

MARKING ASIAN/PACIFIC AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH, MAY 2021, WITH RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS ABOUT MY YEAR IN JAPAN

By Ed Lenci, incoming Chair of the International Section of the New York State Bar Association, and Partner, Hinshaw & Culbertson LLP, New York City

I crossed a personal Rubicon in 1984, during the first semester of my senior year of college. I decided not to go directly to law school but, instead, to spend a year in Japan as a kenkyūsei (research student) at ICU (International Christian University) in Mitaka, a city in Tokyo’s metropolis. I had a number of reasons for my decision. My Dad was a retired General Motors exec and, before he retired, a common topic at the dinner table had been competition from the Japanese automobile industry. Additionally, I had read in newspapers and magazines that Japanese businesses were strongly emerging in a variety of areas and could supplant U.S. dominance in some. Furthermore, my favorite courses in the previous three years had focused on international history, relations, and law, and I hoped to pursue an internationally focused legal career. It made perfect sense to me, therefore, to travel to Japan to meet and learn about the Japanese. Because I didn’t speak Japanese, ICU was ideal because many classes were taught in English and ICU’s Japanese language program was considered one of the best in Japan. Alea iacta est!

Some here in the U.S. were thunderstruck at my plan. Anger at the Japanese – and, in some cases, hatred – was strong in the U.S., particularly in my parents’ generation. It resulted from a caustic combination of the impact the competition from Japan had on a breadwinner’s ability to provide for his family and memories of the Second World War that my parents’ generation had fought.

This anger even trickled downed somewhat among my peers, particularly the children of those who had fought in the war. Undeterred, I headed to Japan in August 1985.

Upon arrival at Narita Airport, I managed to get myself from there to Tokyo but was bewildered how to get to Mitaka. A Japanese man came up to me and asked me, in English, if he could be of help. I explained my problem and he said to follow him. This man helped me purchase a train ticket and then showed me to the correct train, which he, too, boarded. I had just assumed it was his train, too; but, when we arrived at Mitaka, he detrained with me, approached and spoke briefly with another man, and got back on the next train going back toward Tokyo. The second man escorted me to my new landlord’s home. To this day, though interrupted by the pandemic, my radar is set for bewildered tourists or other visitors to New York City to whom I pay forward the kindness of those two men who helped me on my first day in Japan.

ICU was founded in 1949 by Americans and Japanese and its mission was to promote international reconciliation, peace, cooperation, and understanding. The student body is multi cultural, comprised of Japanese students and students from other nations and cultures who live, study, work and have fun together. Additionally, a number of courses, such as history, economics, and politics, are taught in English and gaijin (foreigners) like me could study the Japanese language in an immersive setting. ICU’s Japanese students study English and had a bounty of English speaking students, like me, with whom to practice. I had chosen the right place.

For an activity, I joined the Shorin-ji Kempo club. Shorin-ji Kempo means “Shaolin Temple boxing,” a temple and a form of fighting known in the U.S. from the popular 1970s TV show “Kung Fu.” Shorin-ji Kempo caught my interest because I had studied martial arts, on and off, in high school and college. My Japanese teammates were both male and female and they welcomed me and the other gaijin who joined. We all quickly became friends who enjoyed many outings that usually ended up at a watering hole. My Japanese teammates called me “Edo,” which was amusing to their ears because Edo is also the former name of Tokyo and an important period in the history of Japan. I became friends with other Japanese students, too. I realized through these friendships that, cultural differences and their expression aside, Japanese college students were no different than their American counterparts; we all liked to have fun together and had the same hopes, dreams, and fears about the future.

A few weeks after classes began, I saw a notice in an English-language newspaper about a weekend for English speakers at a Zen temple about an hour by train from Tokyo. I signed up and it was the first of a number of visits to Zen temples while I was in Japan and the start of a personal practice of zazen (seated meditation) and mindfulness (called awareness at the time) that has proved highly beneficial to me over the years. Based on my experience, I have long believed that meditation and mindfulness can be an antidote to anger and hatred. I believe also that such practices should be part of a high school, even a middle school, curriculum, and I’m pleased that many law firms, including my own, now offer training in mindfulness and meditation. Why do I think so? First, if practiced regularly, zazen gives the practitioner a stark, unobstructed view of her or his own thoughts and thought-processes. All thoughts, including judgments, biases, prejudices, and fears, are observed during meditation and ultimately recognized for what they are: purely constructs of one’s own mind, with no substance or independent reality. In other words, the practitioner comes to understand that negative emotions and reactions are all in the mind. Second, through meditation and mindfulness, the practitioner develops self-restraint, especially the ability not to act or react in anger or hatred.

My weekend visits to Zen temples prepared me for one of the great experiences of my life: a homestay during the New Year’s holiday at a Zen temple in a remote, rural part of Kyushu, the southern of Japan’s four main islands. My family for that ten days were the Oshōsan (abbot), his wife, and his teenage daughter. Oshōsan, as I called him, took me on his daily rounds to visit families in nearby villages. I was something of an oddity – a hair under 6’ tall, 200 lbs., wearing a peacoat and sporting a beard – but I was universally welcomed, though some small children cried at the sight of me. The highlight of my stay was when I was given what I believe was a rare honor, to process and sit for a sacred meal with Oshōsan and his fellow priests at a funeral at Rakan-ji, a unique Zen temple that emerges from the mouths of numerous caves on a mountain’s rockface. I was glad I had learned, during my weekends at temples, the table manners and etiquette used at sacred meals, and several of the priests were amazed that I knew proper etiquette.

One of the most important lessons I learned during my year in Japan was that what we in the U.S. consider rude is simply not rude elsewhere, and vice versa. When visitors or newcomers to our nation say or do something considered rude here, we should pause to consider that it’s quite likely that the speech or behavior in question is not rude in their nation of origin and they mean no offense. For example, it was not the way in Japan for a man to hold the door, carry heavy bags, etc., for a woman. Japanese women often showed a combination of amusement and embarrassment when I opened a door, motioned to go first, and said dōzo osakini (“please go ahead”) or just dōzo (“please [go ahead]”), and I ultimately restrained that instinct. (NB: I realize many women today consider these practices sexist). The most amusing of my lessons in this particular cultural difference involved carrying shopping bags for Oshōsan’s wife and daughter after we had checked out at the local supermarket. I instinctively grabbed the two largest bags and, as we were heading to their car, a number of teenage lads were in stitches. When I later asked Oshōsan’s daughter why they had laughed, she explained that Japanese men don’t carry shopping bags. I apologized and explained that, where I lived, it was rude for a man not to carry the bags, or hold the door, for a woman. She said with amusement that she hoped Japanese men would do the same someday.

To earn money, I taught English. One of my students was the lay director of Sanko-in, a Buddhist temple and convent that served shōjin-ryōri, the vegetarian cuisine served at Buddhist temples and convents. The director was studying English because she and the Anshusan (“abbess”) were planning to visit the United States to promote the English version of the cookbook, “Good Food From A Japanese Temple,” that Anshusan and her predecessor had written. During one of our discussions, my student told me that her husband was a hibakusha, a person physically affected by the atomic bombings, in his case, of Hiroshima. I asked what he thought about her learning English and travelling to the United States. She said he had no animosity toward Americans and was pleased she was learning English and travelling to America. I told her of the continued anger among many Americans about the war, and this puzzled her because the U.S. had won the war. Given the attitudes in the U.S., her observation was a blink moment for me.

After I returned to the U.S., I entered Columbia University School of Law. After my first year, I had the great fortune to work for the summer at Hamada & Matsumoto, now Mori, Hamada, & Matsumoto, in Tokyo. I wrote partly of that experience, another of the great ones in my life, in “Introduction to The Rule of Law In Japan: Hon. Hamada Kunio’s Keynote Address.”

In November 2019, the International Section of the New York State Bar Association held its annual global conference in Tokyo. The theme of the conference was “A World of Many Voices, United in Our Diversity.” Asian Pacific Island American Heritage Month is one of a number of reminders throughout the year that we should unite in our diversity and not fear it. Such celebratory months should inspire all of us to enrich not just our communities, not just our nation, and not just our world but also our very own selves, by learning about, getting to know, and becoming friends with people of different cultures.

I’m grateful to my friend and former Chair of the International Section, Diane O’Connell, and my friend and colleague, D. L. Morriss, who are also the Diversity Officers of the International Section, for encouraging me to write this and for their advice.

Thank you for your kind attention.