Alumni Stories No. 14 – Dr. Hisato Yamaguchi

Dr. Hisato Yamaguchi majored in physics at ICU and graduated in 2001. He currently resides in New Mexico and works as a researcher at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Here is his profile and an article about an award that he recently won. Please enjoy his “ICU story.” (All photos were provided by Dr. Yamaguchi.)

There are two important things that I have gained at ICU. One is a sense of how to flourish amidst diversity, and the other is life-long friendships. I am a material scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in the U.S. and in this article. I would like to go over my career trajectory, touching on specific examples of how ICU impacted it. I hope to provide prospective ICU students a real-life story of an alumnus, and for others, a chance to learn about the unique education that ICU offers.

First of all, why did I apply to ICU? Well, because it was a natural thing for me to do. I attended a Japanese public high school, but classes did not interest me at all, because neither the teachers nor the students seemed to be intrinsically interested in the topic of study. As a result, I focused my attention on extracurricular activities, devoting all three years of high school to establishing a tennis club, and entering and winning an essay competition hosted by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). ICU was known for its unique liberal arts education that was outside the box, so applying to ICU was a natural course of action.

I felt at home from the first day at ICU. This is probably because ICU students had their own thoughts, and the community was small with only 700 students per year. I already knew in middle school that I wanted to become a researcher, so I devoted my time to physics research at ICU. I started research experiments at the beginning of my junior year, a year earlier than other students. I would start my day at 9 a.m. and spend all of my time on research except when attending classes and club activities, go back to my dorm at 2 a.m. only to return at 9 a.m. the next morning to continue my research. I had no sense of the day of the week because of this intense schedule. However, I enjoyed this life because I was always with my laboratory mates. Outside of class, I played ultimate frisbee. There were only just enough people to make a team, but I was always throwing a frisbee on the lawn in front of the main building (called baka-yama) whenever possible. Interestingly, I am still playing ultimate frisbee in my free time in Los Alamos despite its 7,200 ft altitude and low oxygen concentration. We have many talented players. I feel very fortunate to have this wonderful ultimate frisbee community despite the isolated location.

Life in the1st men’s dormitory had a huge impact on me. My father lived in a dormitory when he was a college student, so he gave me one condition when enrolling at ICU, which was to live in a dorm. At the dorm, I was always with dormmates and there were so many events throughout the year that I had no time to study there. In addition, because there was so much diversity in the dorm (at least compared to the Japanese public high school I came from), there was no discipline whatsoever. I feel that I gained the ability to survive in chaos during my time in the dorm. My former dormmates have become a TV producer, business consultant experts, banker, accountant, visual media artist, author, magazine editor, university faculty (teaching Middle Eastern culture, Indian philosophy, and chemistry), global tour guide, Ministry of Foreign Affairs official via 10 years in South Sudan and Palestine as an NGO employee, MEXT official, prefectural official, and university administrator. There is no other time in my life when I was surrounded by such a diverse group of people. At the time, I had no idea how living in such chaos would benefit me, but now I realize that it was one of the most valuable times of my life.

I came to the U.S. after obtaining my PhD, and my ICU connection played an important role in determining where I would go. Goki Eda, who was an undergraduate student in the same laboratory at ICU when I was pursuing my master’s degree was a graduate student at Rutgers University at the time, and he recommended me to his supervisor. They were studying a novel material called graphene, which is an atomically thin sheet of carbon. The material was discovered in 2004 in the U.K. and the discoverers were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010, only six years later. Having the privilege of working on this novel material at a relatively early stage greatly impacted my research career. Not only was I able to work on a promising novel material, the supervisor of the laboratory was an exceptional scientist with a vision. He was a young assistant professor at the time, but is now a full professor at Cambridge University. It was from him that I learned every skill that I needed to be competitive in global research. Goki has risen through the ranks and has become one of the most active and well-known young researchers specializing in graphene. He was awarded an extremely generous research funding of over two million U.S. dollars from the Singaporean government and is continuing his research as a university faculty.

When I applied to a competitive fellowship provided by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, my ICU connection helped me again. Susumu Yamamoto, my former dormmate, advised me through the process and I was awarded the fellowship. Susumu got his PhD from the University of Tokyo and went on to do research at Stanford University. Recently, when I performed experiments at a facility called SPring-8 in Japan, he was working there as an assistant professor and I had the chance to meet him 20 years after graduation. He is now an associate professor at Tohoku University and seems to have some interaction with my longtime collaborator there, so I may have more opportunities to see him in the future.

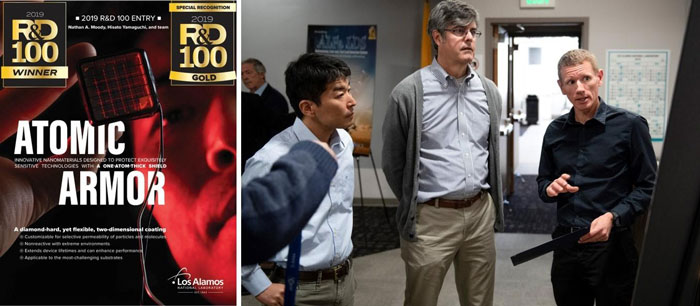

My current employer, Los Alamos National Laboratory, is a large research institution with 10,000 employees that covers a broad range of research topics; biology-related topics such as HIV and biosensors, environment-related topics such as air and soil pollution, advanced material-related topics such as nano-, optical and magnetic materials, applied material-related topics such as mechanical strength and aging of metals and their alloys, nuclear physics and nuclear materials, space-related topics such as satellite orbital calculations and development of scientific instruments for Mars exploration missions, and components development for accelerator technologies. My role as a material scientist at the laboratory is to provide solutions to any material-related problem that rises in various divisions. Working in a place like Los Alamos National Laboratory reminds me of my time at ICU, when I worked with people with diverse backgrounds and personalities in the dorm, clubs, intensive English classes and general education classes to achieve common goals. It also reminds me that I gained my core education at ICU. Let me share an example. I have been leading a project related to an accelerator technology as an expert on graphene. In this project, we need technical expertise on physics, chemistry, electrical engineering, materials science etc. to solve the problem. This means is that the success of the project largely depends on how well we function as a team. The differences in specialty, cultural background and personality make collaboration a challenge, but I am able to enjoy dealing with complex situations due to similar experiences at ICU. This attitude helps me capture team members’ strengths early and manage how they can effectively contribute to achieve the project goals. As a result, our project succeeded and won a prestigious and competitive invention award at the end of last year. The award was featured on the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) website, and our team participated in an award ceremony at the Los Alamos National Laboratory hosted by our director, in addition to the official ceremony held in California.

I will conclude by mentioning my friendships with ICU graduates. It took quite a bit of effort to become a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, and I must admit that I did think about quitting research a number of times. ICU friends were important people who supported me through those hard times. Yu Suzuki is one example. He was my colleague and laboratory mate in physics major for both undergraduate and graduate studies at ICU. He now works for Sumitomo Corporation in a department related to automobiles. He recently moved to Detroit as a part of his job and came to visit me in Santa Fe. This spring, he will enroll in a computer science master’s program as a part of his job to study artificial intelligence (AI). His plan is to utilize scientific knowledge to improve functionalities of future automobiles including safety. Ryoei Hirano played ultimate frisbee with me throughout my years at ICU, and now works in the financial sector as a manager to design a software system for a company. He is also a top professional mahjong player in Japan. He was recently transferred to New York City and sent me a pudding from a famous cupcake shop in NYC. I also have contact with Takamitsu Ito, who I met at a summer seminar for physics majors at ICU’s Karuizawa Campus. He obtained his PhD at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is currently an associate professor at Georgia Institute of Technology. When I was struggling to get a job, he gave me kind words which kept me going.

I hope you enjoyed reading my story and gained some insight into what ICU has to offer.