Alumni Stories No. 16 – Mr. Shinichi Hirabayashi

Mr. Shinichi Hirabayashi graduated from the College of Liberal Arts in 1963 and the Graduate School of Public Administration in 1965. He was the President of the ICU Alumni Association of the Americas in the early 2000s and recently joined the JICUF Hachiro Yuasa Society through a commitment of a bequest. We are excited to share his story.

I attended ICU for six years through both the College of Liberal Arts and the Graduate School of Public Administration. Coming from rural Nagano, I strived to support myself by working three evenings a week as a private tutor as well as a teacher at a prep school in Nozaki, Mitaka. One day, my senpai, Sadami Wada (ID 1960), who was about to graduate, asked me to take his place as an instructor at the English Conversation Class at Ginza Church. I was astounded and flattered but broke out in cold sweat from anxiety. I lived off campus and was a member of the Glee Club and Motor Club. In the Glee Club, I thoroughly enjoyed the regular concerts in the fall, frequent part practices in D-kan, and the summer camps in Karuizawa. A mini-concert that we had in the public hall in my hometown Saku City, Nagano, is a fond lifelong memory. In the Motor Club, I revelled in crazy ‘figure 8’ driving in the tall grass behind the honkan. When I graduated, I was given a card signed by all of the members with one of them addressing me as a “Motor Club member without a driving license”: I had no idea anyone knew! That was the moment I felt indebted to Toshiaki Taguchi (ID 1964), the club leader, for letting me “graduate” from the Club without obtaining a license. (I had an opportunity to pay him back 39 years later.)

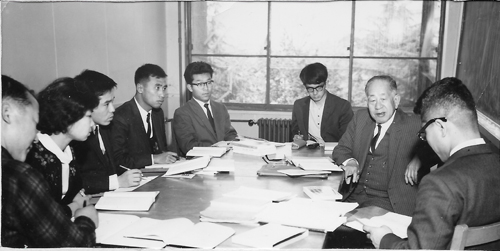

At ICU, I majored in political science with a minor in sociology, and studied public administration in graduate school. From my sophomore year on, I received financial aid through work as a summer field research assistant to a sociology professor, and as a research assistant at the ICU Social Science Research Institute as well as an assistant to an American visiting scholar at the Research Institute of Labor Management at Keio University. After GSPA, I aimed to study in the U.S. and was appointed the Rockefeller Regional Studies Fellow at Princeton University Graduate School. I received a Fulbright travel grant, and came to the U.S. in the summer of 1965. After a month-long orientation program in Hawaii, I arrived in Princeton, NJ. I made the journey to New York with my ICU classmate Takeo Uchida via the West Coast and Chicago/Detroit. Takeo was heading to Tufts University, MA.

The three years at Princeton were full of both joy and pain, but the faculty, students and campus were all first-rate and I was greatly inspired. Graduate students went to dinner every night wearing a black academic gown, a tradition I could never get used to. On weekends, undergrads cheered on the football team waving signs with an upside down Y, the symbol of rival Yale. I watched in amazement at their fervor.

At the time, the U.S. was in a dark period between the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King just two years prior and the assassination of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy three years later. Sociopolitical chaos was intensifying by the day. Under such circumstances, I could not feel happy even if I got decent grades for my classwork or term papers. The global political and economic paradigm was breaking down with the escalation of the Vietnam War, and studying the academic theme that I selected, “Development Administration and Political Modernization,” was like attempting float fishing in a turbulent muddy stream. It became clear that it was not the right time to pursue this theme. I pondered if I should shift my specialization from public administration to political sociology or international relations to continue pursuing academia, or switch my goal to another profession. Up until this point, the balance sheet of my life was completely unbalanced, showing only liabilities. I asked myself how I could put into practice the creed that I acquired at ICU, which is to appreciate the kindness and help I received and return them to people and society. Although it was painful to let down the people who had supported me until that point, I decided to move away from academia and become a business specialist rooted in American society.

With a new goal, I set my sights on the U.S. State Department as a place to gain field experience through active participation rather than remote observation. I passed the State Department’s interpreter’s exam and participated in the Cultural Exchange Program. Then I worked for the Consulate General of Japan in New York for two years and learned about the business modes and achievements of local subsidiaries of Japanese companies. What caught my attention was how the top executives of Mitsui & Co. U.S.A. (Mitsui USA) took leadership among the local Japanese business community and widely interacted with various civic organizations. Mitsui USA originated in the New York branch of Mitsui & Co. established in 1879. Its presidents have historically served as the Nippon Club chairman or the president of the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industries in New York. As Japan’s economic power ascended rapidly, the prominent roles of Mitsui USA put its presidents on the map among the U.S. business circle. This led me to aspire to work for Mitsui, and I got a job at their NY Head Office. Shortly after, I was offered to change my status to a regular employee of Mitsui & Co. and was assigned to Corporate Planning. My classmates at ICU, Shohei Rokumoto, Noboru Kawasaki, and Tomoo Takebe had joined the company ten years before me. There was no way I could catch up with them, so I decided to distinguish myself by working as a genuine Mitsui USA man instead of following in the traditional footsteps of a business sector man.

In retrospect, I was fortunate to have a career at Mitsui & Co., whose modus operandi was ”Challenge and Creation” backed by its “free and open-minded” corporate culture. Such an environment afforded me the chance to exercise my creed to serve people and society through my work across the Pacific. My work entailed frequent travel between New York and Tokyo. In Tokyo, my main job at Mitsui & Co. was to serve as staff assistant to the top management including the president, chairman, ranking advisers, etc. in their activities concerning Japan’s economic relations with such countries as the U.S., Canada,and Australia. As my first assignment, I accompanied Chief Adviser Tatsuzo Mizukmi to a joint steering committee meeting in Hawaii to prepare for the next Japan-U.S. Business Conference. The next one was to accompany Chairman Eiichi Hashimoto who served as the Deputy Head of a Business Delegation to Canada, dispatched by the Japanese government, to make a three-week caravan from Vancouver to Ottawa, meeting with all of the provincial governments and major business organizations.

In New York, I worked for seven years as the general manager of the corporate planning department, which was the longest that anyone had served in the position. Amid trade frictions erupting with Japan’s rapid economic rise and the hardening of U.S. policy towards Japan, I thought hard about what a trading company should do.

One thing I did was to actively publicize Mitsui’s achievements. The company’s export performance ranked fifth in the U.S.A. and it contributed two to three billion dollars annually to the U.S. trade balance. The company also gave back to U.S. local businesses, labor and civic life through operating nearly 200 subsidiaries and related companies. I made a wide range of efforts including arranging seminars to support various state offices’ trade and investment promotion efforts, and presentations in business schools across the nation.

At the company, my routine work included the compilation of short and mid-term profit plans, coordination of business strategies in the Americas, presiding over the review board of hundreds of loan and investment proposals, and processing several thousand ringi applications over the years. Through these back office actions, I believe that I contributed to minimizing losses and increasing profitability for the company. However, I did not see this as serving people and society. I was determined to turn Mitsui USA into a first-rate company recognized for its social contribution, and to build the necessary infrastructure and manage it. Mitsui USA had already been making sizable disaster relief donations and widely supporting both U.S. and Japanese civic organizations. Its presidents had tried to be flexible in meeting social needs while prioritizing profit. When the then President Mamoru Tabuchi joined the Avon Company’s advisory board and dedicated his adviser’s fee to the pool of future donations, it gave me an ideal opportunity to realize my dream of creating an infrastructure for promoting good corporate citizenship of the company.

Immediately, I submitted a ringi to establish the Mitsui & Co. (U.S.A.) Foundation, Inc. as a window for Mitsui USA’s social contribution, and it materialized in 1978. Since the start of its operation in 1979, the Foundation has been engaged in active interaction with and support for various local institutions. We have grown to run 50 continuous programs each year, including scholarships for about 100 college and graduate students in 21 states, hosting 15 “Mitsui Forum” (lectures series) at four universities, supporting regular events such as the March of Dimes Walks. We also instituted a matching program for employees’ donations and incentives for volunteer activities, opened Mitsui USA Creative Arts Center at Mercy Home for autistic children, hosted monthly dinners for the elderly, and developed joint projects with branches and subsidiaries.

From the onset, I was in charge of operation of the Foundation, but in the 15 years before my retirement in 2011, my management philosophy as the CEO was that the Foundation’s donations were not just a sign of the company’s goodwill but a social investment from which we had to reap an appropriate ROI. Return meant the success of the recipients of our donation. My responsibility was to facilitate their success and let it serve as a testament to the company’s good corporate citizenship. This would be my way of serving people and society.

Lastly, let me return to how I paid back my friend Taguchi san.

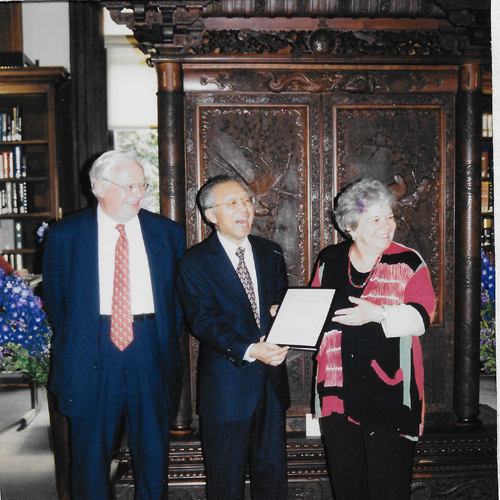

In 2001, I was extremely busy managing the Foundation and concurrently working as the executive director of the Research & Public Affairs Center of Mitsui USA. Taguchi san was then the president of Toyota Motor North America, Inc., and he was soon to become the next president of ICU’s Alumni Association in the Americas (ICU-AAA), based in New York. However, Taguchi san asked me to assume this post as he could not due to unexpected circumstances. I humbly declined multiple times, but finally yielded to accept when he even approached my boss to persuade me. I ended up serving for two terms, four years total. What I aimed to do as president was to vitalize the organization and promote activities to support our alma mater through closer cooperation with JICUF. I sought to communicate this through my messages in the JICUF Newsletter between 2002 and 2004.

As I reached the age of retirement, I left Mitsui & Co., Mitsui USA and its Foundation. It was a long journey across the Pacific, but the reason why I was able to work as a true New York-Mitsui man was because I had roots in ICU, and am deeply grateful for that. Late last year, I pledged a bequest to JICUF, and was invited to join the Hachiro Yuasa Society. I was honored by this unexpected invitation, and Yuasa sensei must be quite surprised to see me join. Thank you for reading my story.