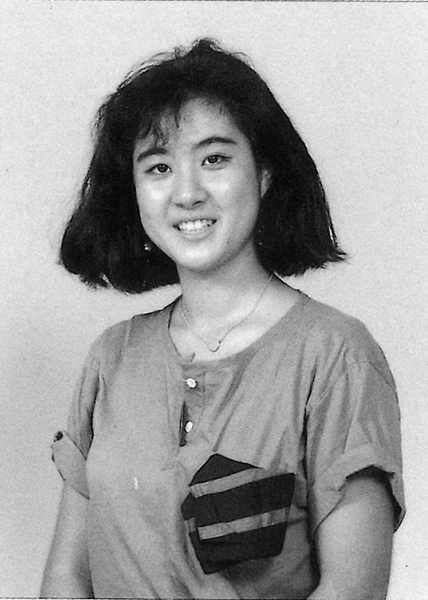

Alumni Stories No. 6 – Ms. Chizuko Muranaka Broinowski

This month, we asked Ms. Chizuko Muranaka Broinowski (ID 88) to look back at her time at ICU. After graduating from ICU, Chizuko attended two graduate schools in the U.K. and earned master’s degrees in communication and journalism. She worked in journalism for many years, and lived in New York for over a decade. She currently lives in Lausanne, Switzerland, with her family, and works as a freelance interpreter.

ICU, Where It All Started – Transformation Through a Paradigm Shift

ICU is a small universe in itself. Faculty and students with unique personalities were shining like bright stars. Through a tunnel of cherry trees in full bloom, I walked along the kassoro (runway) on to the campus. At the matriculation ceremony in the university chapel, I signed a pledge to uphold the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This was the first time I had to sign anything. “Something new and big is happening.” My premonition came true.

I grew up near a fishing town in Kamakura, and the ocean was my friend. I was admonished as an impudent girl for questioning a senior teacher and I was skeptical of public education that regarded entering the University of Tokyo as the ultimate success. I was interested in politics, and although I thrived in English class, I was not particularly interested in English literature or the English language. I wanted to use English as a tool, and ICU seemed like the best match for me.

Since I was little, I had dreamt of living abroad and getting to know different cultures. At ICU, it was refreshing to mingle with section mates who were returnees, and be exposed to their fluent English and openness. In the fall, I was even more surprised by the September students who confidently stated their opinions mixing English and Japanese words. I got used to the categorizations at ICU such as “non-Japa (non-Japanese)” and “han-Japa (half Japanese).”

Before entering ICU, people told me I was “strange” when I voiced my opinions, but at ICU, everyone was “strange” and I felt right at home. One day, Kyoko, a sophomore who grew up in New York, said to me, “You don’t have to use keigo (honorifics) to me. I’m no different from you.” I felt a shock as if Bakayama had flipped upside down. This was the first paradigm shift I experienced.

The three-hour commute from Kamakura to ICU was a pain and a waste of time. Kamakura was deemed “too close” to enter the dorm, so three months after matriculation, I rented an apartment in Kamirenjaku with my high school friend, Emi. It had two hachi-jo (15 square meter) rooms. Every morning, we’d take turns going to our part-time jobs at a nearby bakery, and cycle to ICU. My life centered around the campus which was 20 minutes away by bicycle, attending classes, practicing with the Modern Dance Society (MDS), and cooking dinner at home.

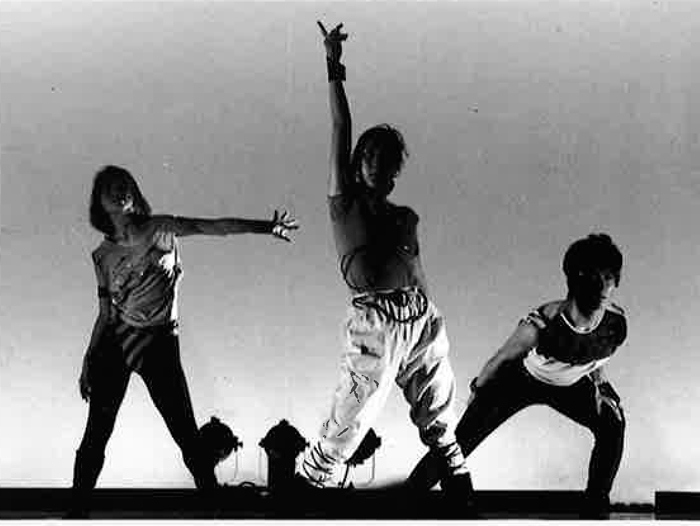

“Bunburyoudou” (excelling in both academics and sports) was the motto of Shonan High School in Kanagawa that I attended, and I tried to do exactly that – work hard and play hard. The carefree days of studying what I liked and enjoying my leisure time glow in my memory. The classes taught by Professors Yoichiro Murakami, Yozo Yokota and Kiyoko Cho caused an intellectual paradigm shift. After their classes, I felt that my mind had expanded and soared. The Modern Dance Society (MDS) was another place where I literally soared into air. The stage was another important part of my life.

I was captivated by the magical sense of being one with the audience and creating a space together. I played Captain Hook in the performance of “Peter Pan,” and choreographed and danced to heavy metal music. I joined Melody Union as a singer too, and taking part in the musical “The Rocky Horror Show” was an unforgettable experience. I was determined not to miss classes, and sometimes attended classes with a thin layer of clothing thrown on top of my leotard, for which I was admonished by a professor. With the hope of meeting people outside ICU, I also joined a ten-university joint seminar to discuss international politics. It was fun to collaborate with students from different universities and across grades, and I was blessed with good friends.

Just when I reached a point where I felt I had performed in enough shows, and started to feel that ICU was getting too small in my third year, I had the opportunity to study in the U.S. Partly due to advice from Professor Yokota, I decided to study at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

During the next ten months, I saw both the light and dark sides of American society. UMass has a nickname, Zoo Mass, and it was indeed full of remarkable students. My 17-year-old roommate Sue hard-sprayed her blond hair and wore heavy blue and pink eyeshadow. Sue laughed saying “When you first saw me, you jumped out of your chair!” On campus, the political leanings and attires of students differed in each dorm cluster. When the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees played against each other, a racially-charged clash occurred between the white fans of the former and the black fans of the latter, which led to the police intervening. Security service was available when moving around campus at night, and everything I experienced was unimaginable at ICU.

In P.E., I took scuba diving and dance classes because I thought I wouldn’t have to speak English. In a class I took with an African American friend from Boston who was the first in her family to attend college, the only people of color were her, me, and the instructor, who also happened to be African American. After class, the three of us danced in front of the mirror. I felt that dance was a tool to express both joy and internal conflict. I was excited by Alvin Ailey Dance Theater’s performance on campus, but was perplexed when a white student asked me if I wanted to “become black.”

One of the main reasons why I chose to study at Amherst was because I could take classes in five prominent colleges in Pioneer Valley in Western Massachusetts. The other colleges were small and quiet, and was similar to ICU in terms of the interests and academic standard of students. It was refreshing to get on a bus and leave Zoo Mass at times too.

At Amherst, I took a class taught by Professor Anthony Lake, who was Director of Policy Planning in President Carter’s Administration and later became President Clinton’s National Security Advisor. My mind and heart danced again, as I was exposed to his critical analysis of the Reagan Administration’s Latin America policy. At Hampshire College, I didn’t know how to counter the argument that the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be justified on the basis that they prevented many more casualties from a ground war. I couldn’t even explain that my inability to refute the idea did not mean that I consented. Thinking of the hibakushas, I was overcome with frustration and tears filled my eyes.

I was always looking for new places and stimulation. I hopped on a long distance bus to Manhattan, where everything glittered – Broadway, dance classes, museums. However, when I stayed at the Spanish Harlem home of Johnny, whom my friend introduced me to, his mother was doing the laundry by hand in their bathtub. His taxi-driver father slept on the couch, and his sister, who was a teenage mom, had left home. Everyone in the family protected his seven-year-old little sister Raquel, who played the old piano in their living room, from the streets.

At UMass, I took classes in journalism and women’s studies and felt like a journalist. The desire to write about what I saw in Amherst and New York, and describe both the light and shadow of society, grew stronger. On the plane from New York back to Japan, I cried. I returned to my conservative family, but my family was shocked that I had turned into this Americanized hippie.

When I returned to ICU in the fall of my senior year several days a week, it felt comfortable but small. To master English as a communication tool, I took Professor Mitsuko Saito’s interpretation class. I majored in international relations and wrote a senior thesis on the U.S. withdrawal from UNESCO under the guidance of Professor Yokota, which marked the end of my days at ICU.

I continued to train as an interpreter after graduation under Professor Saito, but I wanted to “speak my own words” and found a job at SONY where I marketed TV to international clients. In my second year at SONY, as I began to feel fulfilled in my job, I received a Rotary Scholarship with the condition to study in the U.K. I studied communication and media analysis at Center of Mass Communication Research at Leicester University Graduate School and obtained a master’s degree. I went on to do another master’s in journalism at a graduate school in London, at which time I started working for TBS Europe as an assistant to earn my living. After graduation, I became a rookie reporter at the London Branch of Yomiuri Shimbun. My position was correspondent assistant and satellite edition reporter. Through this job, I learned about British traditions and history, and felt that I had attended some sort of social and cultural finishing school. Japan increasingly became attractive viewed from outside.

I returned to Tokyo and became a writer for Yomiuri’s English language paper, but I switched jobs again in 1997 when I felt like moving abroad and experiencing a new field. I was employed by Fujisankei Communications International, the U.S. subsidiary of Fuji Television Network and analyzed media strategies for the headquarters and wrote columns on U.S. broadcasting and New York culture. I enjoyed New York life which I had longed for, and married an Australian whom the first female VP Sales at CBS Station Group introduced me to. I gave birth to two boys, and in fall 2009, my book “New Yorker ha Dokomade Gouyokuka (How Greedy Can New Yorkers Be)” (Fuso-sha) was published. This book was like the senior thesis of my New York life, and I moved to Lausanne, Switzerland.

I became freelance for the first time in my life, and now work mainly as an interpreter. It is thrilling to see the frontlines and backstage of diplomacy and business from a viewpoint that is different from a journalist’s. Last year, I felt a mystical connection when I simultaneously interpreted now UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake’s speech at the UN Human Rights Council.

“Who am I, and what makes me who I am?” Now that I do not belong to any organization, these are the questions I ask myself. ICU will always be where it all began. If I could go back to ICU, I’d like to live in a dorm and enjoy taking classes and performing on stage for a few more years.

Thank you, Chizuko! We hope to see you in New York again soon.