JICUF Grantee Spotlight: Project on Inclusive Education by Miyako Watanabe

This spring, ICU undergraduate student Miyako Watanabe was awarded a JICUF grant for her project titled “Towards the Design of Feasible Inclusive Education in Japan — Education that Embraces Each Individual.” Inclusive education is a reform process in education that ensures the attendance of diverse children in local schools, regardless of nationality, race, language, gender, economic status, religion, or disability. We asked Miyako about her project and what she took away from it.

JICUF: You are conducting research on inclusive education, but what inspired your interest in this topic?

Miyako: In a service learning course at ICU, I learned that other countries had different approaches to inclusive education. I encountered the term inclusive education for the first time in ICU’s entrance exam. An interviewer used the term when she asked a question about an essay I wrote on the unlicensed child care facility I attended called Ringonoki Kodomo Club (Ringonoki). Children aged 18 months to six years attended Ringonoki, and those with and without disabilities spent time together. Later at ICU, I learned more about inclusive education through classes and activities, which further piqued my interest. In the winter semester of my first year, I did community service learning at the Ringonoki, focusing on inclusive education. While children with and without disabilities were treated equally at Ringonoki, the fact that they were completely separated after entering elementary school raised questions in my mind, leading me to explore inclusive education further.

JICUF: Last year, after learning that Minami Sakurazuka Elementary School in Toyonaka City, Osaka, implemented inclusive education, you visited the school. Tell us about that experience.

Miyako: When I found out about Minami Sakurazuka Elementary School through a TBS documentary titled “The Impact of Inclusive Education,” I wanted to visit the school. My mother, an occupational therapist, knew Professor Reiko Ichiki, a visiting researcher at Toyo University. Professor Ichiki introduced me to a teacher at Minami Sakurazuka Elementary School, and with the principal’s permission, I was able to visit the school. I remember the principal being very warm and accommodating.

My first day at the elementary school was filled with surprises and marvel. Having been raised in an environment where children with disabilities were separated from others, it seemed like a dream that those who needed medical care, those who were visually impaired, had Down syndrome or developmental disabilities, as well as non-native Japanese speakers were learning side by side at this school. At Minami Sakurazuka, children with disabilities are officially enrolled in special classes but study in the same space as children without. Last year, I primarily focused on supporting students who were outside of the classrooms,* providing supervision and assistance with assignments. Initially, I struggled with my role at the school and how to interact with the children (such as whether it was better to encourage them to return to the classroom). However, as I explored the teachers’ approaches, I decided to do what I could and make an effort to connect with the children by respecting their feelings. (*Children who found it difficult to stay inside the classroom for a long period of time were allowed to visit the principal’s office or the playroom and work on their own.)

JICUF: This year, you received the JICUF grant and visited Minami Sakurazuka Elementary School again. Were there any differences that you observed this year?

Miyako: Last year, I observed the education in all grades at the school. This year, I decided to focus on specific students in addition to examining the overall approach. The significant difference between last year and this year was the ability to sense the growth of individual students. During this visit, I primarily observed A, a student requiring medical care, B, a visually impaired student (completely blind), and C, a student newly enrolled in the support class. In particular, I noticed substantial growth in C. Last year, C often stayed outside the classroom and resisted returning to class. However, this year, I saw C willingly trying to return to the classroom and making a dedicated effort. This progress was likely influenced by the trust built with the homeroom teacher and support class teacher. C and the teachers review C’s achievements each day. C is aware that they are making an effort spontaneously and not because they were told by others, and the acknowledgment from the teachers and parents seemed to be bolstering C’s confidence.

JICUF: What do you think are the strengths, weaknesses, and challenges of the inclusive education practiced at Minami Sakurazaka Elementary School?

Miyako: I’m sure everyone’s perceptions vary, but the most significant strength I felt was how the environment and education at the school have become normal for the students. This applies to both children with disabilities and their classmates. They have grown up together from their first day of school, attending classes and spending time together, which has naturally fostered their relationship. Regardless of disability or nationality, being together with each other has become natural for them, and they don’t perceive the notion of disability or difference. For example, there was an event in A’s class. I was wondering how A would participate in a game similar to tag, when one of A’s classmates said, “I’ll push A’s special needs stroller” and joined in. They found a way for A to participate, not because they were prompted by adults, but because they always spend time together. Children’s relationships with each other are invaluable. They understand each other’s feelings, personalities, and how to interact.

On the other hand, the challenge lies in the need for a significant number of teachers. At Minami Sakurazuka, students who are registered in special support classes study in regular classes. Therefore, the classes are organized with homeroom and support class teachers working together. The Ministry of Education recommends that students in special support classes receive more than half of their weekly class hours in special support classes, tailored to their individual needs, and encourages students who do not need to spend more than half of their time in special support classes to transfer to regular classes. If the latter were implemented, the number of support class teachers who were in regular classes would be significantly reduced, potentially exacerbating the teacher shortage. I believe that a sufficient number of teachers is necessary to provide individualized education.

JICUF: Practicing inclusive education in schools in urban areas with a high student-to-teacher ratio and a shortage of teachers presents many challenges. Where do you think one should begin to address these challenges?

Miyako: This is a challenging question, but I believe that increasing teachers’ understanding is the first step. When I speak with teachers and students about students with disabilities, I often hear that they are unsure about how to interact with them. However, it’s natural to feel unsure, given the diverse personalities, disabilities, and languages involved. I think that the willingness to understand the students and their unique characteristics is important. Throughout my two years of observing various settings, I have realized that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. While there are guidelines for dealing with disabilities, they may not necessarily apply to all students, so it’s essential to consider individual needs. In addition, working together with other teachers is crucial. In Toyonaka, various actors such as teachers, parents and social workers and other community organizations collaborate to cater to each student. I believe that cooperation with others is the key to implementing inclusive education.

JICUF: After working on inclusive education for two years, did your research focus change?

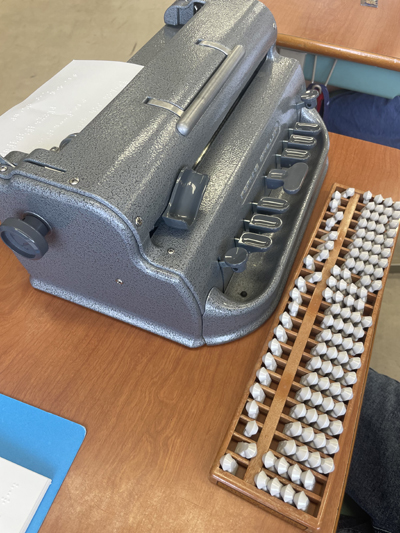

Miyako: Although I’m not sure yet, I’ve developed a desire to support children with developmental disorders. In 2023, the Ministry of Education announced that 8.8% of elementary and middle school students in regular classes may have potential developmental disorders that affect their learning and behavior. The challenge I see is that support is lagging. Some children with developmental disorders have the urge to leave the classroom or find it difficult to be inside. I believe that one of the reasons for this is the classroom environment. Therefore, as a first step, I want to work on creating classrooms with reasonable accommodations. For instance, a classroom that resembles that in Finland, where no child is left behind. Finland guarantees that every child receives individual education in regular classrooms with reasonable accommodations, regardless of disabilities. Each classroom is equipped with items like earmuffs for children with auditory sensitivity, movable partitions for visually sensitive children, sofas for children who find sitting for long periods uncomfortable, and balance chairs that prioritize ease of study.

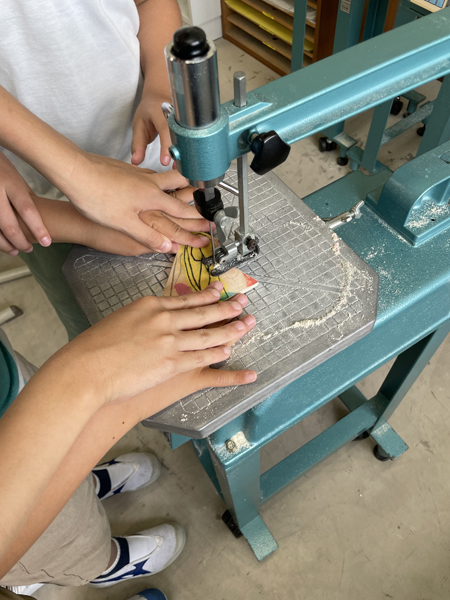

In fact, Minami Sakurazuka Elementary School incorporated reasonable accommodations such as creating partitions at the back of the classroom for children with developmental disorders, which increased the time some of these children spent in the classroom compared to last year. The partitioned space includes desks and chairs, allowing the students to choose a study location that suits their preferences. Toyonaka City’s education system is my ultimate goal. Toyonaka City’s education with the motto “Learning Together, Growing Together” has a 50-year history, and the city’s support for schools is well-established. Achieving this goal won’t be easy and will require time, resources, and municipal and administrative support. So we need to introduce inclusive education gradually. Of course, every child with a developmental disorder is different, so personalized support will be required in addition to building classrooms with reasonable accommodations. Pursuing a comfortable environment for every individual, regardless of whether or not they have a disability or their nationality, will eventually make such an environment the norm.

JICUF: Would you like to share anything else about your project?

Miyako: What was the most striking to me was that the children at the school understood inclusive education. Since last year, Minami Sakurazaka Elementary School has received attention from television stations such as NHK. Researchers had already been visiting the school, but recently, there has been an increase in visitors from the television and education industries. Because of this attention, the children have come to realize that their school is special.

A classmate of student B, who has spent time with B since kindergarten said, “Being together with B is natural, and we don’t want to be separated. For B to not have the option of going to a regular middle school isn’t right.” B has decided to attend a local middle school, but B mentioned that they would not have liked it if there wasn’t that choice.

Furthermore, when one child asked another, “What makes you uncomfortable when you hear the terms ‘inclusive education’ and ‘people with disabilities’?,” the response was, “I don’t understand the concept of coining the term ‘people with disabilities’.” When I asked, “What term would you use instead of ‘people with disabilities’?” they replied, “Everyone is a friend, everyone is a companion, everyone is friendship.” I realized that they didn’t have the word “disability” in their vocabulary. Additionally, that child mentioned that their goal was to promote inclusive education. It’s surprising that they already understood the concept of inclusive education, and I was delighted to know that they wanted to expand schools like theirs with the knowledge that Japan generally practiced separate education. I am excited about what they will do in their future, and it inspired me to work even harder.

♠♠♠♠♠♠♠♠

Minami Sakurazuka Elementary School was featured in an NHK program which can be viewed on youtube.

Thank you Miyako!